VICTORIA -- The United States Navy is in hot water with conservationists over its plans to begin a battery of weapons tests in the Pacific Northwest this fall.

Marine researchers in British Columbia and Washington state say the tests will cause significant harm to mammals on both sides of the border. Of particular concern is the testing program's impact on the endangered southern resident killer whale population in the Salish Sea.

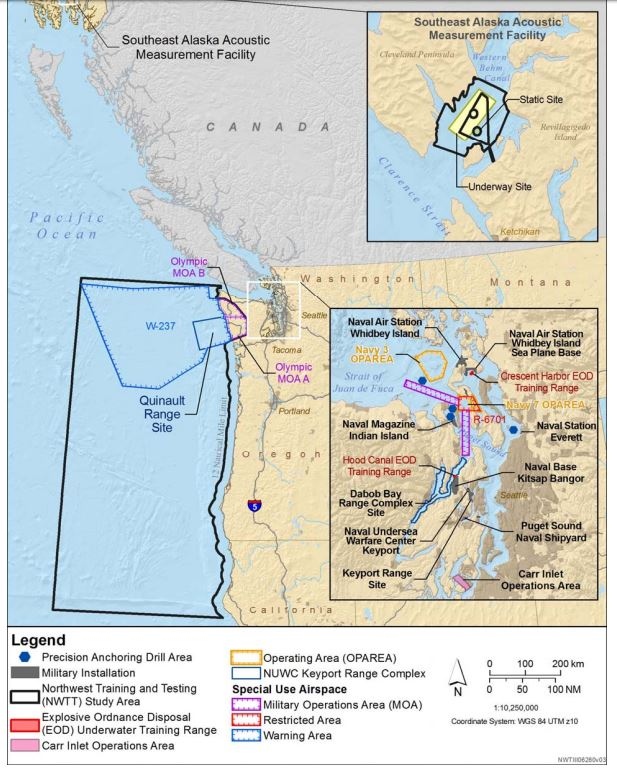

The tests involve launching torpedoes, detonating 450-kilogram bombs, piloting undersea drones and firing missiles and large-calibre projectiles into the ocean and straits off Vancouver Island and northwestern Washington.

The navy doesn’t dispute that all this will pose significant risks to wildlife, including the endangered southern resident orcas.

The naval force has applied to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to begin the tests in November. The application, which is now under review, estimates that 51 orcas a year will be negatively affected over the course of the seven-year program.

It's a stark increase from the two disturbances per year the navy has been granted in the past, and conservationists say the timing couldn't be worse for the southern residents, whose numbers have dwindled over the years to 72 left in the wild.

"The southern residents are an incredibly small and incredibly endangered population of animals," says Deborah Giles, a research biologist at the University of Washington's Center for Conservation Biology.

"For the (U.S.) federal government to be entertaining this in a way that right now seems like it's going to be rubber-stamped through, it doesn't seem prudent for a population that is so small."

The navy says it does not anticipate killing any southern resident orcas, and will instead limit its harm to the species to "Level B harassment," which includes inducing temporary hearing loss and disrupting feeding, breeding and migration patterns.

More than 1.7 million other marine animals are expected to suffer the same harassment level, according to the navy's estimates. Thousands more mammals, including sperm whales, porpoises, sea lions and seals, will be subjected under the program to more rigorous harm – known as Level A harassment – which runs the gamut from permanent injury up to and including death.

The NOAA's preliminary findings in June ruled the navy's tests would have a "negligible impact" on the southern resident orcas, and the agency is expected to greenlight the tests in the coming weeks.

'The timing is horrible'

Michael Jasny, a Vancouver-based director with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), compares the regulatory oversight of the program to "a canary trying to regulate a gorilla," and is calling on the Canadian government to intervene.

"You’ve got a combination of more harm at a time when some truly iconic species shared by the U.S. and Canada are already in crisis," says Jasny, a legal expert with the NRDC's marine mammal protection project.

"What's different this time is the amount of harm is significantly greater and the timing is horrible," he says. "This is a moment when the navy and the U.S. agency that is charged with protecting marine species should be looking for ways to reduce harm from the activity and yet what we're seeing is the opposite."

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has declined to take a position on the tests, with a spokesperson telling CTV News that "DFO and our U.S. management agency partners share the goal of southern resident killer whale recovery and are working closely to support this endangered species."

Officials in Washington state are taking a harder line with the navy.

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, along with the state's attorney general and several agencies tasked with protecting wildlife, are calling on NOAA to deny the navy's application and impose stricter limits on the testing to protect the southern resident orcas.

"Simply put, Washington considers the level of incidental takings of marine mammals in the proposed rule to be unacceptable," Inslee wrote in a July 17 letter to the agency.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife called the anticipated approval a "gross neglect" of NOAA's responsibilities "to this highly endangered and iconic species."

'It's an eye-rolling sort of assumption'

More than two dozen conservation groups have also written to the regulator, saying that increasing the harassment of the southern residents from twice a year to 51 times a year will pose a "population-level" danger to the species.

"Level B harassment means disruption of natural behaviour patterns such as feeding, surfacing, nursing, breeding, sheltering or migration to the point where those patterns are abandoned or significantly altered," the conservation groups noted in a July 17 letter.

"These are all critical activities for the southern resident orcas now, given that they have produced only two surviving calves in the last four years and nutritional stress is recognized as a primary threat to the population."

Southern resident killer whales are listed as an endangered species by federal agencies on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Canadian DFO both say noise and boat traffic are largely to blame for their declining numbers from a peak of 98 animals in 1995.

Jasny, the NRDC director, says the navy's estimates of harm to the southern residents during the tests are a gross undercount, and the activities risk setting back the work the government of Canada has done to protect the mammals.

"The navy assumes – and (NOAA) adopts this assumption – that its explosives activities, its underwater detonations, will not result in any mortality, arguing that the navy's monitoring effort is sufficient to eliminate all risk of mortality and that is nonsense – it's an eye-rolling sort of assumption," he says.

The U.S. Navy tells CTV News it is "keenly aware of the challenges faced by the southern resident killer whales from a multitude of human activities, and focuses considerable effort on avoiding or minimizing potential effects on the species in planning for its at-sea activities throughout the region."

Navy spokesperson Julianne Stanford says the force is working with NOAA to "determine if any additional measures may be practicable to implement to reduce further potential effects to southern resident killer whales."

The federal regulator is now considering the comments it received during its public input period as it prepares its final ruling.