VICTORIA - British Columbia has become the first province in Canada to declare a public health emergency after a dramatic increase in the number of overdose deaths from illicit drugs such as fentanyl.

Medical health officer Dr. Perry Kendall said 201 overdose deaths were recorded in the first three months of 2016 and that 64 of them involved fentanyl. Fentanyl is an opioid-based pain killer roughly 100 times stronger than morphine.

“At this rate, the total for 2016 could exceed 700 or even 800 (deaths),” he said Thursday, adding the numbers are increasing despite outreach initiatives, awareness campaigns and the rapid distribution of the drug naloxone, which reverses opioid overdoses.

Fatal overdoses have steadily increased in B.C. since 2010, when 211 people died, reaching 474 deaths in 2015, Kendall said, adding fentanyl was associated with a third of the deaths.

“The numbers are unusual and unexpected, which is a criteria for declaring an emergency under the Public Health Act,” he said.

Health Minister Terry Lake said the declaration will allow health officers to collect real-time information to help them identify patterns and quickly respond with prevention programs by targeting certain areas and groups of people instead of waiting for data from the coroner's office.

“We have to do everything we can to stop this toll,” he said. “This is a public health crisis and it's taking its toll on families and communities across our province.

Recreational drug users may cut or manipulate a fentanyl patch or smoke a gel form of the drug.

The provincial government said overdoses are only reported now if someone dies, and there is some delay in the information being received from the coroner's office.

Under the state of emergency, information on the circumstances of any overdose where emergency personnel and health-care workers respond will be reported as quickly as possible to medical health officers at regional health authorities. That information will include the location of an overdose, the drugs used, how they were taken, and the age and sex of the person who has overdosed.

Kendall said the province is increasing access to opiate substitution programs by making suboxone available, for example, in an effort to deal with overdose deaths.

A recent British Columbia study suggests a pain medication called hydromorphone could be used to treat heroin addicts who sometimes unwittingly end up with fentanyl in their drug of choice.

The Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse says that between 2009 and 2014, the latest numbers available, toxicology tests from fatal overdoses showed fentanyl was present in 1,019 deaths in Canada, with more than half of them occurring in the latter two years.

Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia have also begun distributing naloxone kits to individuals and first responders to reverse opioid overdoses, said Dr. Matthew Young, a substance abuse epidemiologist at the Ottawa-based centre.

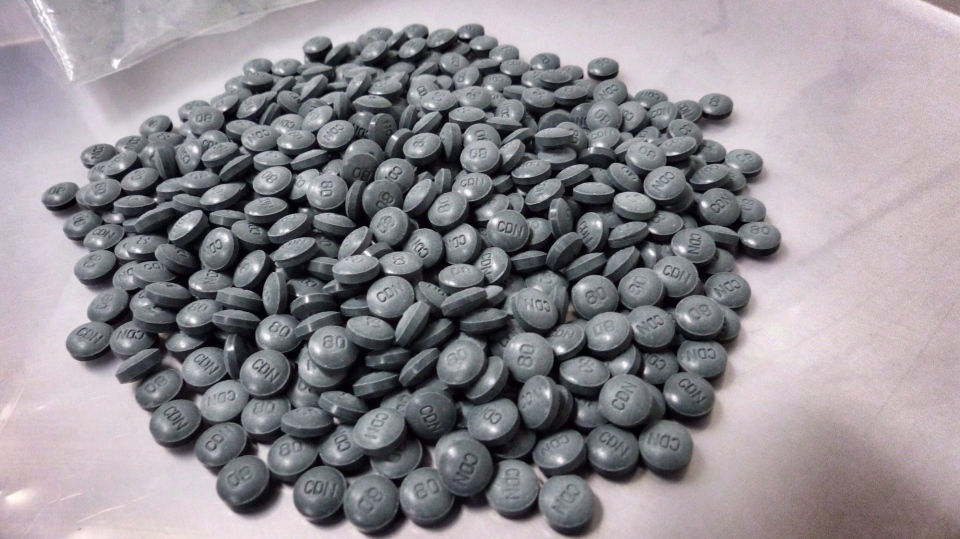

Fentanyl can be deadly because people often don't know it's been cut into drugs such as fake oxycodone, heroin or other pills and powders, he said.

“When it's mixed into these tablets it's highly variable from one to the next. So an individual who uses a pill they bought off the street that contains fentanyl may crush up a tablet, inject it and be fine but with the next one they do they may overdose.”

Young said fentanyl is cheap to manufacture and is often brought into Canada and the United States from China, while Mexico is also a source of the drug in the U.S.

An increase in prescription pain killers such as oxycodone in the mid-2000s to about 2010 is believed to have created more dependence before a public health crisis led to initiatives to reduce such prescriptions, Young said.

“That also created a market where organized crime stepped in and started selling these counterfeit tablets containing fentanyl.”