VICTORIA -- An updated report into anti-Indigenous racism in British Columbia’s health-care system finds that Indigenous people have less access to primary care doctors than non-Indigenous British Columbians.

The data report released Thursday is part of a broader investigation into anti-Indigenous racism in the health-care system launched last year by independent investigator Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond.

The initial report found "hundreds of examples of prejudice and racism" in health facilities across the province when its findings were released in November.

The report, titled "In Plain Sight," was the result of an investigation into allegations that emergency room staff were playing a racist game to guess the blood-alcohol level of Indigenous patients.

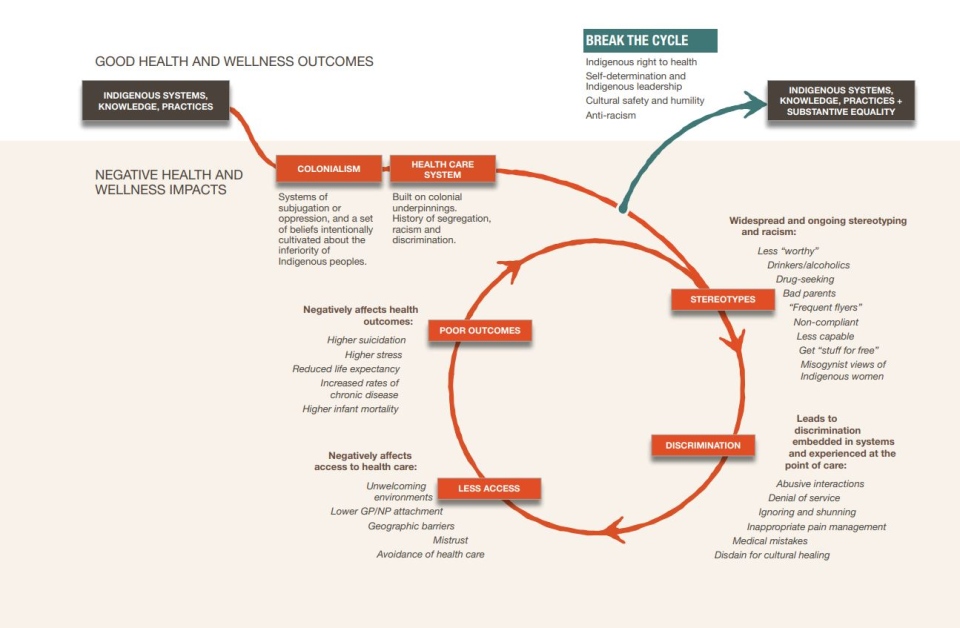

Thursday’s update revealed that a lack of access to primary care physicians is contributing to poorer health outcomes for Indigenous people.

“The inadequacy at this time of B.C.’s primary care system is evident,” Turpel-Lafond said Thursday. “There’s a high burden of disease amongst Indigenous peoples in British Columbia and First Nations people in particular of all ages have comparatively lower attachment rates to GPs – general practitioners – and nurse practitioners.”

The investigation found that far more Indigenous seniors do not have a primary care provider than non-Indigenous seniors. “That, in fact, is quite a staggering finding,” Turpel-Lafond said.

The report found that Indigenous people in B.C. have lower rates of cancer screening than non-Indigenous people. It also found that Indigenous women died of opioid overdoses at nearly twice the rate of non-Indigenous women in 2020.

“There will need to be substantial work done to come close to achieving equality,” Turpel-Lafond said.

“The health-care system in B.C. is a much different experience if you’re an Indigenous person than a non-Indigenous person,” she added.

Health Minister Adrian Dix said recommendations from the report are being implemented, including the creation of an Indigenous health officer and an associate deputy minister of Indigenous health.

“Racism is toxic for people,” Dix said Thursday. “Systemic racism requires systemic action”

The supplemental report is based on results of surveys and patient complaints, as well as hard data on how Indigenous people use health care and the outcomes they experience.

Almost 9,000 people directly shared their perspectives through surveys and submissions, while approximately 185,000 Indigenous individuals are reflected in the health sector data.

Indigenous survey respondents were significantly more likely to feel unsafe in health facilities. For example, in emergency rooms, 16 per cent felt “not at all safe” and 57 per cent felt “somewhat unsafe,” compared with five and 38 per cent of non-Indigenous people, respectively.

Twenty-three per cent of Indigenous respondents reported they “always” received poorer service than others, with 24 per cent treated as though they were dishonest, 26 per cent treated as if they are drunk or asked about substance abuse and 14 per cent were treated like bad parents.

Some 67 per cent of Indigenous respondents reported they had experienced discrimination from health-care staff based on ancestry, compared to five per cent of non-Indigenous respondents.

In fact, only 16 per cent of all Indigenous respondents reported never having been discriminated against for any reason listed while receiving health care.

Turpel-Lafond's team also conducted a survey of health-care workers, of which 35 per cent said they had witnessed racism or discrimination directed to Indigenous patients, family or friends. The number increased to 59 per cent for Indigenous health-care workers who responded.

The report also examined health-care data in the province and found Indigenous people have insufficient access to primary care and preventive care, and increased reliance on emergency departments as well as a higher rate of avoidable hospitalization.

Throughout the report, Turpel-Lafond stresses that Indigenous women are at a particular disadvantage.

“Indigenous women experience unique forms of racism within the health-care system and feel unsafe interacting with that system, resulting in less trust - and therefore avoidance of - discretionary health-care services,” resulting in health outcome disparities, she says.

Turpel-Lafond calls on the government to collect system-wide data and monitor indicators including attachment to primary care physicians, use of emergency departments, chronic conditions and maternal and infant health.

With files from The Canadian Press