Vancouver Island beekeepers keep eye on colonies as Prairies report massive winter die-offs

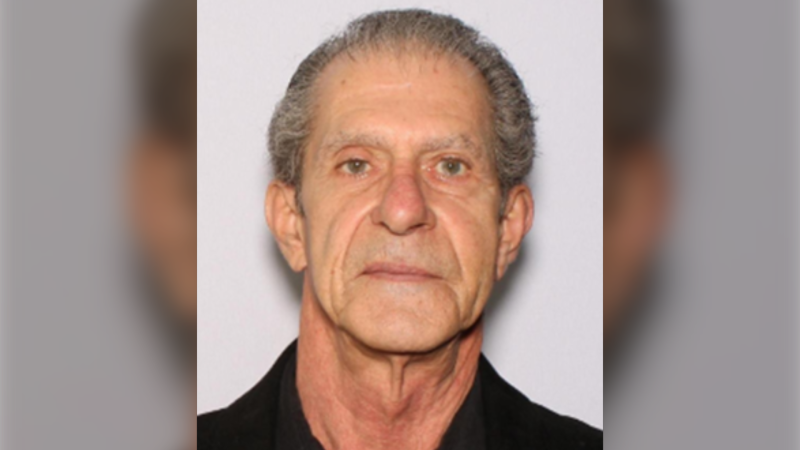

Saanich, B.C., beekeeper Bill Fosdick is about to inspect his backyard hive. It consists of about 1,000 bees.

He's inspecting his bees to see if they've been infected by the varroa destructor mite, a tiny insect which will attach itself to the larva of the bees and slowly weaken some to the point of death.

The mites have become a problem for beekeepers in Canada's Prairie provinces.

"There are certainly producers in the province (of Saskatchewan) who are reporting big loss numbers in the 60 to 70 to 80 per cent of their colonies this year," said Nathan Wendell, president of the Saskatchewan Beekeepers Development Commission.

Back in Saanich, Foswick says his hive appears healthy. His worry though is that the problem on the Prairies could make its way out west.

"One of the things it does is that it opens a doorway to other viruses and infections that can affect the bees," said the beekeeper.

The Prairies could be referred to as our country's breadbasket. Three quarters of the honey produced in Canada comes from the Prairies and bees are also the primary pollinators of many food crops.

"So far the indications for British Columbia seem to be quite promising," said Paul Van Westendorp, the provincial apiculturist of British Columbia.

But that’s not to say we're out of the woods yet.

WINTER COUNTS

The 2020 winter die-off of bees was well above the average of 12 per cent in B.C., and extreme weather events are becoming more common in the province.

"Average winter loss last year in British Columbia was something like 32 per cent," said Van Westendorp. "Thirty-two per cent, that’s almost like one third of the colonies are gone."

For now, this bee expert says we can only estimate what the losses will be this year.

Beekeepers in the province and across Canada will begin officially reporting this winter's numbers next month.

"We may end up having a smorgasbord of numbers, and hopefully the statistics will help us to interpret this in a way that gives us some better picture," said Van Westendorp.

As Fosdick inspects his backyard colony, he says beekeepers on Vancouver Island are small in scale, like his operation.

He says for now, if a massive die-off does happen, it can often be attributed to the producers themselves and not the varroa destructor mite.

"There is no single disease or predator that’s going after honeybees on Vancouver Island that we can say, 'There it is, that’s the problem, we now have to prepare ourselves and defend against that,'" said Fosdick.

Correction

This story has been updated to reflect the fact that bees do not pollinate wheat.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Ottawa injects another $36M into vaccine injury compensation fund

The federal government has added $36.4 million to a program designed to support people who have been seriously injured or killed by vaccines since the end of 2020.

'Secret report' or standard research? B.C. government addresses safe supply allegations

B.C.’s premier and one of his top lieutenants are pushing back against allegations by the Official Opposition that he covertly commissioned a report into the diversion of safe supply drugs onto the streets.

Video shows suspects waving weapons, smashing glass in Toronto jewelry store robbery

Arrests have been made after five men were captured on video rampaging through a jewelry store in Toronto, waving weapons and smashing glass display cases.

'My stomach dropped': Winnipeg man speaks out after being criminally harassed following single online date

A Winnipeg man said a single date gone wrong led to years of criminal harassment, false arrests, stress and depression.

She was too sick for a traditional transplant. So she received a pig kidney and a heart pump

Doctors have transplanted a pig kidney into a New Jersey woman who was near death, part of a dramatic pair of surgeries that also stabilized her failing heart.

What Canadians think of the latest Liberal budget

A new poll suggests the Liberals have not won over voters with their latest budget, though there is broad support for their plan to build millions of homes.

opinion Why you should protect your investments by naming a trusted contact person

Appointing a trusted person to help with financial obligations can give you peace of mind. In his personal finance column for CTVNews.ca, Christopher Liew outlines the key benefits of naming a confidant to take over your financial responsibilities, if the need ever arises.

'One of the single most terrifying things ever': Ontario couple among passengers on sinking tour boat in Dominican Republic

A Toronto couple are speaking out about their 'extremely dangerous' experience on board a sinking tour boat in the Dominican Republic last week.

Teacher shortages see some Ontario high school students awarded perfect grades on midterm exams

Students at a high school in York Region have been awarded perfect marks on their midterm exams in three subjects – not because of their academic performances however, but because they had no teacher.