VICTORIA -- Vancouver Island's history is full of tales of women who were influencers, disruptors and trailblazers, but according to archivists at the Royal BC Museum, many of those stories rarely see the light of day.

"A lot of women's stories have been overlooked and their roles and perspectives have not been documented," says curator Tzu-L Chung.

As Women's History Month draws to a close, CTV News went deep into the British Columbia Archives to shine a light on the stories of island women who overcame so much to make their mark.

Ellen Neel

The reverberations of Ellen Neel's life can be felt any time you see an Indigenous carving, enter a gift shop with Indigenous souvenirs, or see a young First Nations artist pushing the boundaries of their craft.

Born in the early 1900s in Alert Bay, Neel's passion for art flourished in the most difficult of settings.

"She was in residential school, and that is actually where she learned to carve," said Lou-Ann Neel, who is not only a historian with the Royal BC Museum, but also Neel's granddaughter.

Encouraged to carve traditional poles by her father, at a time when women artists were not considered legitimate, Neel's talent quickly put her ahead of most men in the field.

Her work would be sought out by art enthusiasts, museums and collectors around the world.

Even in success, the Vancouver Island born Indigenous artist faced a constant onslaught of racism and sexism as she waded through the male dominated world of art in the mid-1900s.

"I have copies of newspaper articles that read, 'Mr. Neel with his wife assisting.' " said Lou-Ann. "It was this assumption that my grandfather was actually the carver."

Undeterred, Neel broke barriers as she pushed for organizations like the Hudson's Bay Company to purchase handmade art from Indigenous artists and pay them appropriately.

She is considered a major influence in First Nations art being sold in a way which serves not to strip the art from the communities, but to preserve a living culture.

Alma Russell

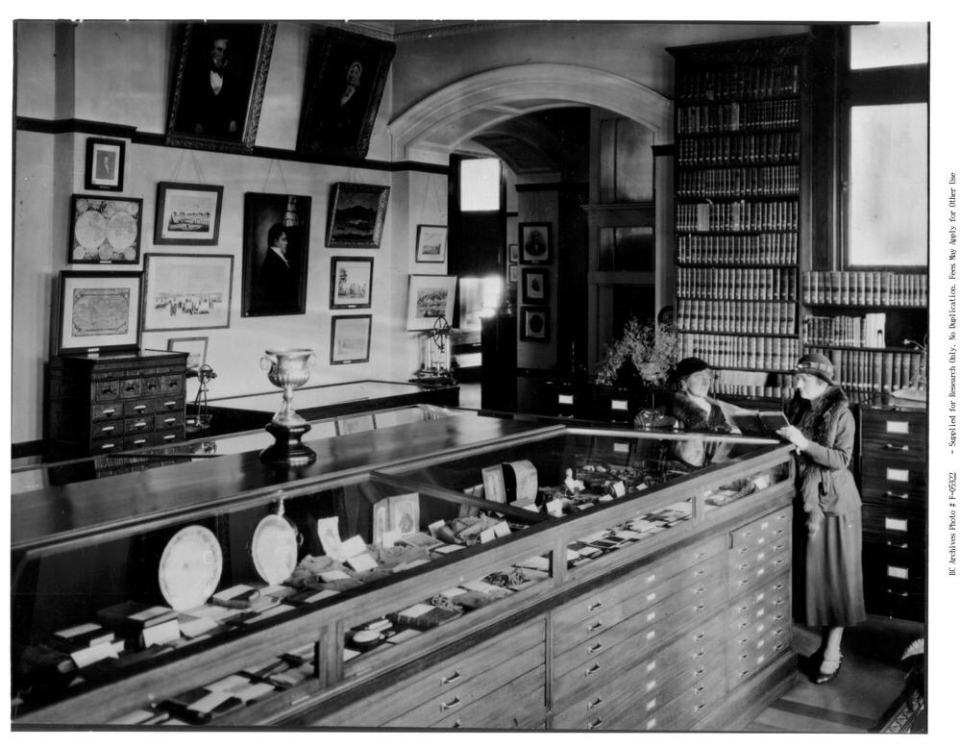

The preservation of British Columbia's history as we know it has a lot to do with Victoria's Alma Russell.

In the late-1800s, the young woman left the comfort of Vancouver Island and struck out in search of higher education.

In New York City, Russell would receive university-level training in library sciences.

Returning home, Russell lived in rarified air.

She was the first person to be hired while having training as a librarian," said B.C. Archives curator India Young. "She is really not just groundbreaking for a woman, but for anyone."

Russell became the first person in Western Canada to receive proper librarian training and was instantly hired by the First Provincial Librarian. "It took decades for her to be offered a full-time job, to be paid adequately," said Young.

Facing the hurdles so many women did in the workplace at the turn of the century, Russell charged on.

She was the first person to institute the use of the Dewey decimal system at B.C. libraries, and also created opportunities for rural communities to access books.

Archivists say she was instrumental in getting literature to places like Duncan, and into the hands of miners working in remote camps.

Seto Chang-Ann

Victoria's Chinatown is known as one of the oldest in North America, but in the early-1900s, as racism towards non-white Canadians ran rampant, it was a rare safe place for the Chinese community.

Inside the small cultural enclave was a woman who strove to educate children and promote the rights of women.

"This was one of the first schools in North America to hire female teachers," said curator Tzu-L Chung.

Chang-Ann, a Victoria born Chinese-Canadian, and her husband were pivotal in raising money to build the Victoria Chinese Public School.

The building is still in operation on Fisgard Street today.

B.C. historians also believe Chang-Ann was influential in making the school the first in North America to name a woman as a teacher.

Alice Ravenhill

Prim and proper, Alice Ravenhill came from high-society England before moving to Shawnigan Lake. But cultural standing didn't stop her from ruffling feathers as she fought for Indigenous rights.

In 1910 , Ravenhill and her family immigrated to Canada. Over the next several decades she would become one of the first authors to document and preserve Indigenous stories from across B.C.

"We really have to remember women like that, who did real work," said Chung.

At a time in Canadian history when the federal government was well know for trying to subvert and disrupt the traditions and lands which First Nations had known for centuries, Ravenhill went into the communities to try and better understand cultural differences.

"She actually acknowledged the way the government perceived Indigenous communities," said Chung. "But also put in real efforts to share the Indigenous voices in arts and crafts."

Ravenhill is remembered for her unwavering dedication to the historical preservation of these communities, and doing it when it was an unpopular practice.