First Nation hunters on Vancouver Island fear legislation will threaten traditional practices

A rifle owner checks the sight of his rifle at a hunting camp property in rural Ontario, west of Ottawa, on Sept. 15, 2010. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

A rifle owner checks the sight of his rifle at a hunting camp property in rural Ontario, west of Ottawa, on Sept. 15, 2010. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Bill C-21, gun control legislation that is currently being considered in Ottawa, was intended to address firearm violence and strengthen laws by controlling handguns and assault rifles. In late November, the Liberal party proposed amendments to the bill that would impact hunters with its broader scope of banning rifles.

At the beginning of February, the amendment that would include some long guns and rifles used for hunting had been withdrawn, though it has been speculated that is only temporary.

For Moy Sutherland Sr. of Ahousaht, he understands the hurt that is associated with gun violence. However, he explains that this legislation impacts people who are honorable with firearms.

“The main priority in our life is not for criminal activity, it's for hunting,” said Sutherland Sr.

He's been hunting for over 65 years to provide food for his family and community. Sutherland Sr. started out in his youth observing his father and brothers when they would hunt.

Hunting was something that always brought him and his family together, a way to connect to their culture as a family utilizing traditional fishing, hunting, and harvesting practices.

The first time Sutherland Sr. shot a deer he was hunting with his father at age 17. His father explained that this would be the last time the boy would watch him field dress a deer.

His father said to him, “from here on in, you are going to always going to work on your own animal,” explained Sutherland Sr. “Every animal you get is your responsibility to work on it that way.”

Sutherland Sr. has gone on to share his knowledge of hunting with his children. His son got his first animal when he was old enough to work on it himself, he explained. Just as Sutherland Sr. had learned, his son would learn to carry firearms and bow and arrows safely, always treating rifles as though there is ammunition in them. Safety was a priority for Sutherland Sr.

“Firearms regulations are always developed by people who automatically think of it as a necessity of criminal life to have firearms and anybody who has firearms is potentially a criminal and that's why the laws are created the way that they do them,” said Sutherland Sr. “They forget about us people that live the way that we do hunting and fishing, what those firearms mean to us to supply food for our family and community.”

When a community member or a family member is struggling with an illness or a loss, Sutherland Sr explains that he helps by offering them traditional food that has been hunted.

Sam Haiyupis, an Ahousaht member, has been hunting since he was roughly 13 years old.

Just as Sutherland Sr., Haiyupus started his hunting journey as an observer of his father and brothers getting bigger animals such as deer or bear. To this day, Haiyupus continues to go out hunting with his brother.

“My whole family would say, depended on different seasons of hunting that we can participate in,” said Haiyupis. “We've always been that way.”

Haiyupis explains that he grew up around his parents plucking, dressing, and preparing ducks that were hunted, together. This is now something that Haiyupis does with his partner.

“They're all my favorite memories because I can pretty much remember just about every year and every place that I caught an animal,” said Haiyupis.

In early December the Assembly of First Nation passed an emergency resolution opposing Bill C-21.

Haiyupis said that he struggles not seeing much Indigenous leadership speaking out about issues involving hunting.

“To me, any rifle, if you're using it for hunting, it's not an assault style, it's a hunting rifle,” said Haiyupis.

He continues that the politicians that are making this legislation don't have a full understanding of rifles, the way that a hunter does.

“We go through all this screening when we do our application for our Possession and Acquisition Licence. And yet, it's not enough that we shouldn't be trusted with what we own,” said Haiyupis.

“We hunt for sustenance,” added Haiyupis. “It's a way of life for us, for a lot of us.”

Darren DeLuca is owner of Vancouver Island Outfitters for the last 30 years. Deluca grew up in Port Alberni where he had access to the backcountry and started hunting with friends as a teenager.

“The amount of time that you spend in the outdoors, and the things you see and experience, you sort of see the glory in nature… both its strength and its fragility,” said DeLuca.

Deluca explains that with hunting, because you are taking the life of an animal, hunters often build a sense of personal responsibility and stewardship towards nature and wildlife.

With Nuu-chah-nulth teachings at the center, Sutherland Sr. teaches respect for the environment, animals that are hunted and the people who are joining the hunt, whether they are elders or the younger generation. Respect is the number one priority, including not overharvesting.

“It's partly also looking after the population of what we're out there for,” said Sutherland Sr.

“The last minute amendment feels like a target on rural communities, and has distracted from the original purpose of the bill,” said NDP MP Rachel Blaney while in the House of Commons.

But Canada's Minister of Public Safety Marco Mendicino stressed that the bill was to target AR-15 style guns, used in previous shootings such as Polytechnique.

For DeLuca, hunting is about going out with friends, families, and sustaining his community.

“The real crime issue is handguns in gangs in the inner cities,” said DeLuca.

“I always see governments trying to restrict hunters' rights, and I never once see them do something to support hunters' rights, bring forward a regulation, or an act that protects a person's right to hunt and fish,” said DeLuca.

“Fortunately, Indigenous people have the constitutional right to hunt and fish,” he added. “In a lot of cases it's protected wildlife, because they had to protect that constitutional right.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

'They needed people inside Air Canada:' Police announce arrests in Pearson gold heist

Police say one former and one current employee of Air Canada are among the nine suspects that are facing charges in connection with the gold heist at Pearson International Airport last year.

House admonishes ArriveCan contractor in rare parliamentary show of power

MPs enacted an extraordinary, rarely used parliamentary power on Wednesday, summonsing an ArriveCan contractor to appear before the House of Commons where he was admonished publicly and forced to provide answers to the questions MPs said he'd previously evaded.

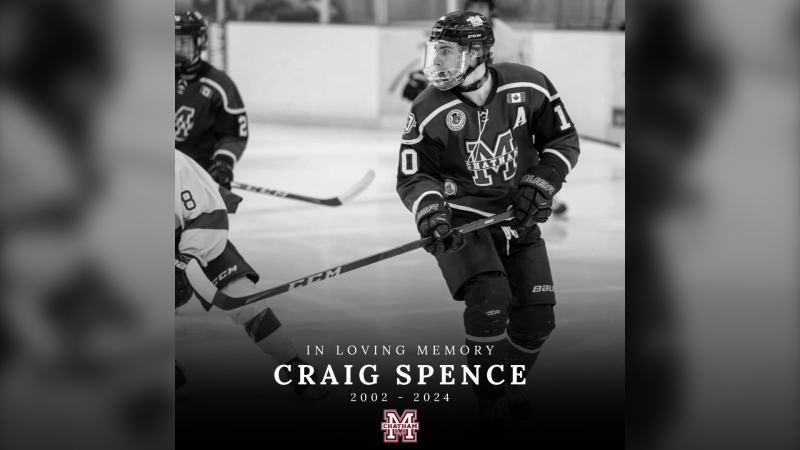

Leafs star Auston Matthews finishes season with 69 goals

Auston Matthews won't be joining the NHL's 70-goal club this season.

Trump lawyers say Stormy Daniels refused subpoena outside a Brooklyn bar, papers left 'at her feet'

Donald Trump's legal team says it tried serving Stormy Daniels a subpoena as she arrived for an event at a bar in Brooklyn last month, but the porn actor, who is expected to be a witness at the former president's criminal trial, refused to take it and walked away.

Why drivers in Eastern Canada could see big gas price spikes, and other Canadians won't

Drivers in Eastern Canada face a big increase in gas prices because of various factors, especially the higher cost of the summer blend, industry analysts say.

Doug Ford calls on Ontario Speaker to reverse Queen's Park keffiyeh ban

Ontario Premier Doug Ford is calling on Speaker Ted Arnott to reverse a ban on keffiyehs at Queen's Park, describing the move as “needlessly” divisive.

'A living nightmare': Winnipeg woman sentenced following campaign of harassment against man after online date

A Winnipeg woman was sentenced to house arrest after a single date with a man she met online culminated in her harassing him for years, and spurred false allegations which resulted in the innocent man being arrested three times.

Woman who pressured boyfriend to kill his ex in 2000s granted absences from prison

A woman who pressured her boyfriend into killing his teenage ex more than a decade ago will be allowed to leave prison for weeks at a time.

Customers disappointed after email listing $60K Tim Hortons prize sent in error

Several Tim Horton’s customers are feeling great disappointment after being told by the company that an email stating they won a boat worth nearly $60,000 was sent in error.