There was no getting away from the tariff issue at the 43rd annual CERAWeek by S&P Global energy conference that wrapped up on Friday in Houston.

The importance of the trading relationship between Canada and the United States—from interdependency on energy, critical minerals and the intertwined supply chains—was emphasized at many of the sessions through the week and in hallway conversations.

It was hard to find anyone who was supportive.

Think about the trillions in market value represented at the conference, all saying the tariffs are bad for the economy.

Without exception, the consequences of the unprecedented level of transactional friction that has been introduced mean one thing—higher costs for everything, including energy, despite the Trump administration’s unrealistic goal of U.S. energy dominance.

Energy dominance doesn’t happen without Canada as part of the equation.

And curiously, there was no reference to Canada’s energy sector in the address by Energy Secretary Chris Wright at the opening session of the conference, which felt much like it was delivered with someone else listening in.

It took Shell’s CEO, Wael Sawan, to mention Canada in the context of LNG Canada coming online later this year.

Without our oil barrels flowing into the U.S. refining complex and the natural gas molecules that support U.S. domestic demand that enables the growth of its LNG exports, the goal of U.S. energy dominance will be elusive.

And while not acknowledged by Wright, Torbjorn Tornqvist, chairman of Gunvor Group, the Swiss-based global commodities trading firm, was emphatic about the impact of the tariffs in the U.S., the importance of the relationship between Canada and the U.S. and why it’s going to hurt the U.S.

“As soon as you start to ‘fix’ something, you create artificial arbitrages, and that’s not good in the long run. Canadian energy is very integrated with North America. The U.S. refiners buy (Canadian) barrels at a cost that’s $15 per barrel cheaper than they export. That’s good business. Why change that?” said Tornqvist during a panel discussion.

Canadian oil, he said, provides the highest value for U.S. refineries.

If they are forced to use domestic oil—in whatever way possible because the refineries are not set up to accept lighter barrels—the costs will rise, which will then be passed on to the consumer.

Also standing in the way of the energy dominance goal is economics.

This was another theme woven into panel conversations because the industry has learned some very hard lessons over the years about pursuing a growth strategy at any cost.

“We won’t be chasing growth for growth’s sake. That’s never been successful for the sector,” said Mike Wirth, Chevron CEO.

In other words, the private sector answers to Wall Street, not the White House.

Trump’s homegrown “drill, baby, drill” approach must make money for companies and shareholders.

And in a world where U.S. shale needs an oil price of about US$80 per barrel, the simple economics of supply and demand point to downward pressure on oil prices if production is increased.

That’s alongside the fact OPEC+ announced earlier in the month that it was going to increase production and global economic growth is at risk.

If anything, companies need durable policy from governments that recognize the certainty required to risk long-cycle capital.

Without it, capital sits on the sidelines, used to buy back shares, pay down debt or increase dividends rather than make investments.

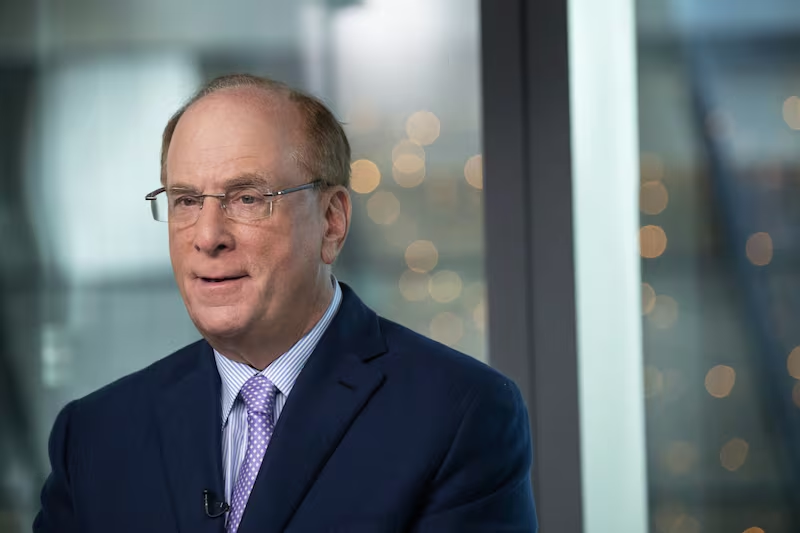

And the importance of private capital in the economy was underscored in a conversation between Pulitzer Prize-winning author, vice-chairman of S&P Global and founder of CERA (Cambridge Energy Research Associates) Dan Yergin and BlackRock’s chairman and CEO, Larry Fink.

With government budgets squeezed, Fink said it’s private capital that is needed more than ever before—to build infrastructure critical to supporting long-term economic growth.

“The need for private capital is greater than it’s ever been,” said Fink, adding that growing the economy by investing in infrastructure is how the U.S. can overcome its burgeoning deficit.

In order to do that, said Fink, companies need durable government policy that they can rely on to make those long-cycle capital commitments and for the numbers to work; short-term fixes are not the recipe.

Think about those three words: durable government policy.

It’s always tempting for new administrations—regardless of jurisdiction—to overturn the policies and regulations of their predecessors simply because it was not their idea.

Trump is no exception.

But the whiplash this creates for companies looking to risk capital stymies investment rather than encourages it, ultimately compromising economic growth and opportunity in response.

And that will also be the outcome of the tariff and retaliation drama around the world if a resolution isn’t found to diffuse the rhetoric and results in a conversation grounded in realistic solutions rather than hyperbolic and unconstructive rhetoric.

As Fink rightly pointed out, what’s happening now is unwinding the global trading systems that enabled inflation to largely remain in check and foster economic growth around the world.

“We are walking away from the themes that kept inflation down. At what cost are you willing to change this? Because the consequences are higher costs,” he said.

And higher costs mean inflation, the prospect of rising interest rates and slower economic growth—for everyone.

This is not what the world needs right now.

History has taught us where this all could lead—it’s time to pay attention to those lessons.